Nine months after 52% of Britons voted to leave the EU Prime Minister Theresa May has, today, notified the European Council of the UK’s intention to exit, triggering Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty. The Treaty provides for a two year negotiation period between the EU and UK to set out the terms of an exit agreement.

Nine months after 52% of Britons voted to leave the EU Prime Minister Theresa May has, today, notified the European Council of the UK’s intention to exit, triggering Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty. The Treaty provides for a two year negotiation period between the EU and UK to set out the terms of an exit agreement.

What To Expect

Setting a Negotiation Mandate

European Council President, Donald Tusk, has said that, within 48 hours of the UK triggering of Article 50, he will present draft guidelines for the negotiation talks to the Member States excluding the UK (EU27). The EU 27 will consider the draft and agree framework guidelines.

The Commission in turn will propose more technical negotiation texts, namely Brexit directives, based on the framework guidelines. Once the texts are approved by the Member States they will form the negotiation mandate, binding the Commission’s chief negotiator, Michel Barnier and the Commission’s negotiating team during the talks.

Timeline

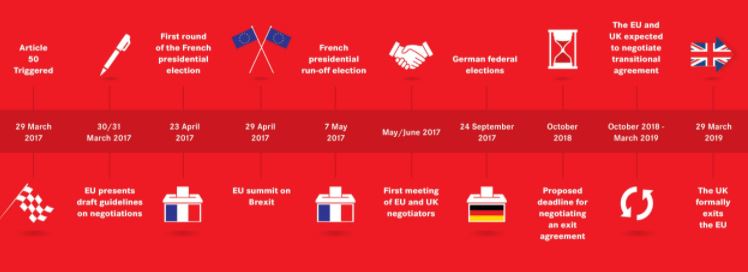

The EU27 will hold its first Brexit summit on 29 April 2017, a date which is sandwiched between the first round of the French presidential election and the presidential run-off election. The successful French candidate’s position on EU integration will inevitably shape the development of the EU going forward. The first round election results could influence the EU 27’s decision to take a “hard” or “soft” approach to negotiations. EU27 and UK diplomats are not expected to meet until late May or June – as the interim period between agreeing framework guidelines and producing a negotiation mandate for Mr Barnier could take six to eight weeks. Mr Barnier is aiming to have the withdrawal agreement drawn up by October 2018, if not earlier, to allow time for the European Parliament to consent to it, and the Council to ratify it. The British Parliament has also been promised a vote on the final deal by Prime Minister May and Brexit Secretary, David Davis.

The UK will formally exit the bloc on 29 March 2019, unless the UK and the European Council unanimously agree to extend the two year limit or to have a transitional arrangement. A transitional arrangement, whereby there would be a period between the current situation and the commencement of the terms of the withdrawal agreement, will be essential to businesses to avoid a “cliff-edge”. It is impossible to say how long this transitional arrangement, assuming there is one, would stay in place. Mr Barnier has said any transitional arrangement will be limited in time, meaning the UK’s exit will not be delayed indefinitely by inadequate infrastructure and incomplete legislation, by either party. Any flexibility regarding the period after the two year time limit must be unanimously decided on by the European Council and the UK – politics, not legalities, seem to dominate Article 50. There is little possibility of a full withdrawal agreement being reached and ratified within the allotted two year time period and some flexibility is almost inevitable.

People, Borders, Money and Trade

In January, Mrs May set out Britain’s priorities for the negotiations in her Lancaster House speech. Last week, addressing the Committee of the Regions in the European Parliament, Mr Barnier seemed to directly respond to the Prime Minister’s speech by affirming the EU 27’s priorities for the upcoming talks.

Common Ground

Securing the rights of over four million EU and UK citizens living in Britain and across the continent is an early priority for both parties. Prime Minister May has called for a "seamless, frictionless border" between the North and South of Ireland. Mr Barnier has echoed her sentiments promising to be “particularly attentive” to the issue.

Not So Common

The EU and UK have expressed divergent views on the structure of the negotiations. The EU has repeatedly emphasised it will approach negotiating an exit deal and a new free trade agreement as mutually exclusive, whereas the UK would prefer that both would occur in parallel. The controversial matter of the UK’s contribution to outstanding liabilities in the EU budget persists. President of the Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker has said the UK has “the choice to eat what’s on the table or not come to the table at all” and Mr Barnier iterated similar sentiments. The UK Government has openly resisted the reported €60billion bill; British chancellor, Philip Hammond, has said he does not recognise the figure, and international trade secretary, Liam Fox, has called the bill “absurd”.

Mr Barnier has rebutted Mrs May’s insistence that “no deal for Britain is better than a bad deal”. The EU’s chief negotiator warned the consequences of a walk-away would be detrimental for the UK, citing lorry queues at Dover, nuclear material shortages, disruption to air-traffic and the return of custom controls. European leaders have sent a clear message to the UK; the new EU – UK relationship cannot be an “à la carte” of Britain’s previous membership rights and obligations, and any new deal must be inferior to that of membership.

It is important to recognise the myriad of complexities of disentangling 44 years of economic, political and societal integration. In turn we should not expect a new free trade agreement and certainty for cross-border business in the immediate future.